I had no idea that February was Women In Horror Month when I first started researching the following article back in September 2016. I was hoping to use it for a blog post in October, but life being what it is, just never found the time to wrap it up. Therefore, instead of holding off on it, I thought it was quite topical for February instead!

As a female horror writer and a long time reader of 19th century literature, mostly along the lines of Bram Stoker, Wilkie Collins, and Edgar Allen Poe, I recently decided it was time to learn more about those ladies who have come before me in the genre. The best place to start was at the beginning, or as near to the beginning as I could find out there. That search led me back to 1778.

Before Anne Rice’s vampire Louis de Pointe du Lac told us all about Lestat in that famous Interview With A Vampire; before Daphne du Maurier introduced us to the cruel and promiscuous Rebecca; and even before the creation of Frankenstein by Mary Shelley in 1816, there was Clara Reeve and Ann Radcliffe. Reeve’s novel The Old English Baron was published in 1778. Radcliffe followed suit in 1794 with The Mysteries of Udolpho.

What passed for horror then is a far cry from what we know today, but the basic elements remain the same. 18th and 19th Century horror was more of the emotional variety. It was a mental state of being linked to unfortunate and seemingly inescapable circumstances. A sense of claustrophobia was key to these novels, be that in a physical sense as in bodily imprisonment or in a mental sense with feelings of madness and mental illness. Today’s version puts the characters in some sort of insane kidnapper’s isolated torture chamber or house of madness trying to escape as one by one as they are bumped off in the bloodiest, most gruesome ways possible. Not quite so with the works of Cleeve and Radcliffe.

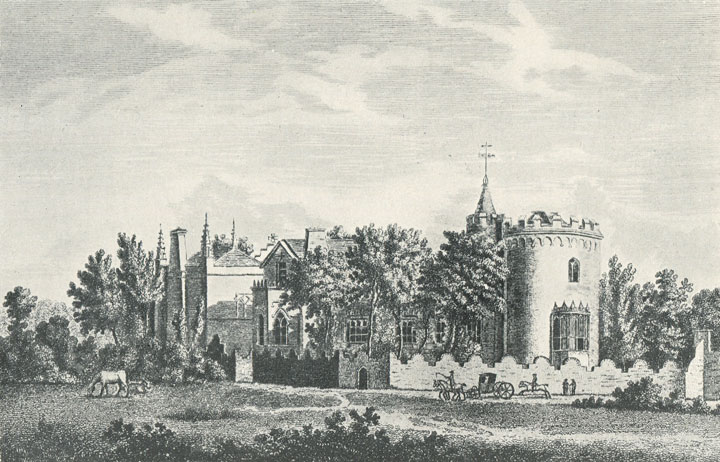

Classic Gothic literature is considered to have started in 1764 with the writing of The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole. Within it contains elements of realistic fiction and romance with overtones of the paranormal. The setting included the now almost cliché isolated castle with secret passages, trap doors, clanging chains, and pictures with eyes that shifted and watched passers-by and set a standard for many, many future Gothic novels. The term Gothic stems from the setting, specifically Gothic-style Architecture that was popular during the high and late medieval period, roughly from the 12th-16th centuries. The most common use for this type of architecture was churches and castles, though hundreds of stately homes and colleges also employed the style.

Clara Reeve was born in 1729 to Reverend William Reeve, M.A., rector of Freston and of Kreson in Suffolk, England and his wife, whose family were jewelers to King George I. Clara did not begin to write seriously until after the death of her father. Originally titled The Champion of Virtue, a Gothic Story, The Old English Baron was written in direct response, and perhaps even as a form of literary rivalry to Walpole’s 1764 novel. Very little is known about Clara’s personal life.

Clara Reeve was born in 1729 to Reverend William Reeve, M.A., rector of Freston and of Kreson in Suffolk, England and his wife, whose family were jewelers to King George I. Clara did not begin to write seriously until after the death of her father. Originally titled The Champion of Virtue, a Gothic Story, The Old English Baron was written in direct response, and perhaps even as a form of literary rivalry to Walpole’s 1764 novel. Very little is known about Clara’s personal life.

Ann (Ward) Radcliffe was born in London in 1764 to William and Ann (Oates) Ward. At twenty-three she married William Radcliffe who was a journalist and Oxford University graduate. As he often worked late and the couple was without children, Ann took up writing to help pass the many hours she spent alone. As with Reeve, Radcliffe left behind scant information about her private life outside her accomplishments as an author.

Ann (Ward) Radcliffe was born in London in 1764 to William and Ann (Oates) Ward. At twenty-three she married William Radcliffe who was a journalist and Oxford University graduate. As he often worked late and the couple was without children, Ann took up writing to help pass the many hours she spent alone. As with Reeve, Radcliffe left behind scant information about her private life outside her accomplishments as an author.

More times than not, the main character is a seemingly hapless and helpless woman destined for a life of misery should things continue as they are. More times than not she is also an orphan. This loss of parents or any sort of close, positive and loving family member to protect and guide her is only the beginning of her troublesome fate. Emotions are the biggest foe as well as the greatest ally to the Gothic Horror heroine. Time and time again she will be brought down, dragged through the emotional mud, her mind and spirit and sometimes her body taken to the very brink of doom and despair. She is ruled over by an iron fist in the form of an older man or woman who wants to control everything she says and does for their own personal gain. Usually, that gain is monetary and comes with an increased level of status. These guardians are actually more like cruel, heartless prison guards. This is where the monsters we’ve come to associate with horror novels and movies today were spawned.

As powerful and omnipotent as these very human monsters appear to be, they have their weaknesses and their secrets. Finding that weakness and unravelling the secrets is the only way the damsel in distress is going to be set free. Most assuredly there is a knight in shining armor out there, because romance is what makes a Gothic Horror, Gothic and not just Horror, but she can’t rely on him to rescue her. And this where those emotions that have so far worked against her, become her greatest weapon. She cannot hope to overpower them physically, but at some point in her upbringing, before she was orphaned and life went to hell in a handbasket, someone taught her some powerful psychological and emotional lessons. She may be poor and she may be destitute, but she’s far from stupid. She must use her wits and beat her captors at their own game. How she does that is what drives the plot forward.

Have you noticed that not once have I mentioned anything supernatural actually going on?

The earliest Gothic novels contained very little in the way of the paranormal. And even if there was a ghost, strict limits were often placed on its behavior. The ghost of Lord Lovel in The Old English Baron for instance, is a silent apparition. He is detectable only by sight, never heard or sensed in any other way and is never brought forward into daylight so we can have a really good look at him. There is no confirmed ghost at all in The Mysteries of Udolpho, but we do catch sight of what may be a corpse wearing a black veil.

For obvious reasons, these sorts of novels were tremendously popular with female readers and were very often targeted towards that audience by first appearing as serials in the leading women’s magazines of the day. Within the confines of the story they could see themselves portrayed as the ‘weaker sex’ and taken advantage of by men, and sometimes other women, of wealth and power. And yet, despite the hardship, there was always hope that the main character would triumph because of her quick thinking. She may be physically weaker, but to see another woman win because of her smarts must have been a wonderful ego boost and given feelings of empowerment to the women reading. If the poor and pitiful Emily of The Mysteries of Udolpho can survive all that she was put through, surely, I, the reader, can overcome my troubles. Feminism was taking root even back then.

From Reeve to Radcliffe, Shelley to du Maurier, Jane Austen and the Bronte sisters up to our current female women in horror, Shirley Jackson, Anne Rice, Anne Rivers Siddons, Caitlín R. Kiernan and even myself, we have all strived to present horror in a way that not only frightens but may also empower our readers. Without consciously trying to target a female audience with my own work, I’ve noticed that the majority of my main characters are very strong-minded women. They face the most bizarre of situations and yet they keep fighting for what is right. They discover their inner strengths as they battle the real or imagined paranormal madness that surrounds them. In that way, I feel I am giving a very respectful nod of recognition to the female horror writers who have come before me and am proud of what I have been able to offer the genre in the past and what I hope to present to it in the future.

If you liked this post, you might find my The Horror of Women blog post of interest, too.

Recent Comments